Contents

- Read in September 2021, in William Cullen Bryant’s verse translation (1869)

- I was surprised how often the warriors pick up rocks and throw them at each other in combat.

- “There are heroes on both sides??” I was surprised how favourably both sides are described. We are not necessarily meant to see the Greeks as the good guys, Trojans as bad.

- Cast of thousands and each character has a back-story. The poet assumes his audience knows them already.

- All are greatly concerned to gain possession of the bodies of the slain

- Not just so that they can obtain the armour, etc., but so that they can possess the body too

- They want to remove the bodies of their countrymen and allies from the field so they can do them honour, and the bodies of their enemies so that they can dishonour them, feed them to the dogs, etc.

- Graphic descriptions of how each man died, who killed him, where the spear pierced him and came out the other side, etc., but also of whom they left behind, wives, children, parents, the pastoral life they had at home, often quite sad

- The Iliad is an elegy of a lost heroic age: how many of these great men died and their like has not been seen since

- Especially when the men pick up rocks to throw at each other, there is mention made of how no men are that strong today anymore

- It was hard to keep track of which gods were helping which side and why.

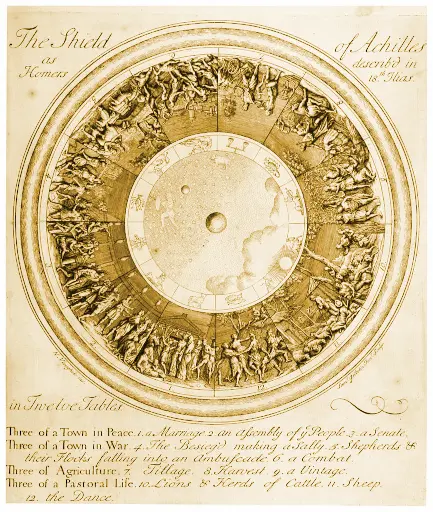

- Was surprised by and enjoyed Book 18’s description of the shield of Achilles made by Hephaestus, with all its depictions (of different aspects of civilization?)

- Book 22, Andromache laments the probably future fate of her son Astyanax, seeing the body of Hector dragged by Achilles, “The day in which a boy is fatherless / Makes him companionless; with downcast eyes / He wanders, and his cheeks are stained with tears. Unfed he goes where sit his father’s friends, / And plucks one by the cloak, and by the robe / Another. One who pities him shall give / A scanty draught, which only wets his lips, / But not his palate; while another boy, / Whose parents both are living, thrusts him thence / With blows and vulgar clamor: ‘Get thee gone! Thy father is not with us at the feast.’”

Fr. Hunwicke

Book 6 compares Hector and Paris, Andromache and Helen; Paris is soft and woman-crazed and Helen is a seductress, corrupt adulterers; the relationship of Hector and Andromache is well-ordered, they fulfill their roles correctly as husband and wife, see the following Fr. Hunwicke articles

- Visiting women in their houses

- Sexual passion is a madness that leads to disaster

- Paris is defeated in a duel with Helen’s lawful husband, Menelaus, but rescued from death by his patroness, Aphrodite, who transports him back to his bedchamber to lie with Helen, while the slaughter continues without

- Paris’ house consists of θάλαμος (bridal chamber, women’s quarters), δῶμα (men’s quarters) and αὐλή (outside courtyard)

- Hector goes in but only as far as the αὐλή, and stands on the threshold of the θάλαμος, looking in

- HOMER’S ILIAD BOOK 6 AND S AMBROSE: Episode 2

- Hector does not go in to the θάλαμος, where Paris and Helen are; in ancient societies, men didn’t go into such areas in the daytime, and at night only with their own wife

- Hector does not even cross that threshold at his own home, and is surprised not to find his wife there; there are very few other places where Andromache would be expected to be

- Expectations of where members of the two sexes would be found, persisted even in the west into the 19th century

- Our current society is the cosmic odd-man-out where men and women can go wherever they want and mix with whomever they want

- Homer’s Iliad Book VI and S Ambrose: Episode 3

- St. Ambrose’s Book 2 in Lucam: at the Annunciation Our Lady was alone in the inmost parts of her home

- At Our Lady’s Visitation of St. Elizabeth, full of joy she went in haste to higher place, to the hill country, she did not tarry in public going about (circumcursare) and gossipping

- Our Lady was late to leave her home and speedy when she was in public

- Our society has completely rejected female modesty, and we force our ways on everyone else, and we are so pleased with ourselves

Lindybeige

- Lindybeige: “A point or two about Achilles”

- Looking at the walls Troy VII, they have a characteristic slope which means it should be possible for Patroclus to climb them

- People offer Achilles incredible bribes to fight, but they never appeal to his sense of duty (e.g. modern times, do it for your country, your king, etc.)

- Achilles had no duty to fight, not part of his culture and he wasn’t fighting to protect his homeland or anything

- he did it for the booty, to sack cities, capture women, and sail home a hero, similarly the Myrmidons are all fighting hoping to get a share of that booty

- Lindybeige: “The Iliad - what is it really about?”

- Wordsworth Classic edition, George Chapman translation?

- The Iliad was a lot like the Bible for the ancient Greeks, library of Alexandria full of commentaries on the Iliad

- Both glorifies war, but at the same time draws our attention to the tragedy of war

- Achilles goes berserk to avenge Patroclus, human-sacrifices 12 captives, lots of cattle, battles the river gods, drags Hector’s body around on the ground from the back of his chariot, buries Patroclus, weeps and mourns, but nothing brings him peace

- Old king Priam’s quiet but brave begging, kneeling and kissing the hands that killed his son, is what finally moves Achilles; giving over the body so that Priam can bury it, an act of mercy, is what finally brings Achilles peace, pointing to a glory that is greater than Achilles’ glory in war

- Perhaps Achilles sees a kindred spirit in Priam’s bravery

John Prendergast

- Iliad Translations: How to Choose the Best Translation of the Iliad

- There are four embassies in the Iliad:

- Menelaus and Odysseus come to Troy to ask for Helen back, in return for peace with the Argives; they are refused, making the Trojans complicit in Paris’ crime

- Chryses comes to Agamemnon offering a worthy ransom in exchange for his daughter; he is refused, bringing the wrath of Apollo on Agamemnon

- Agamemnon sends an embassy to Achilles, offering gifts and apology; this is part of Zeus’ plan to aid the Trojans until Agamemnon and Achilles make peace with each other; Achilles refuses, hoping for an even better offer, one that will perhaps humiliate Agamemnon personally; he is putting himself against the will of Zeus however, and Achilles will suffer for this the next day when Patroclus dies

- Lastly, King Priam comes to Achilles; his offer is accepted and the gods are appeased

- There are four embassies in the Iliad:

Montana Classical College

October 2022, came upon Montana Classical College’s talks on The Iliad. The speaker, Brian C. Wilson has a somewhat illiberal or anti-modern take.

- He has a list of resources here

- Translation he is most familiar with is Richmond Lattimore (1951, line-by-line prose, readable here with as interlinear with Greek)

- “Many of my friends who I think know Homer better than I do have recommended the Caroline Alexander translation (2015, line-by-line prose).”

- “I in this particular reading will be looking at the Robert Fagles’ translation (1990, stacked prose, i.e. prose that ignores Homer’s lines, but is formatted to look a bit like verse), partially because of its ubiquity … and partially because I was curious about investigating it myself.”

Book 1

- The source of the conflict not told in the beginning, begins in mediās rēs

- In the poem the morality and causality is a bit ambiguous, sometimes seems like Paris has stolen Helen, sometimes like Helen left willingly with Paris, sometimes it’s all Aphrodite’s fault

- Achillean epithet “Peleus’ son”

- We see ourselves today as absolute individuals

- But the stress here is that Achilles is part of a family, is relational, is an aristocrat, part of a community; his actions reflect his ancestry and vice versa

- The morality of the Iliad is communal and aristocratic, alien to us liberal and egalitarian individuals

- Peleus is Achilles’ mortal father (as opposed to his immortal mother Thetis); he has inherited death from his father, and this is stated in the opening line

- Kings (Zeus, Agamemnon) do not have their lineage highlighted, at least at the outset

- Subjects do have their lineage mentioned (Apollo, Achilles)

- Achilles’ wrath cost the Acheans “countless” lives

- from Achilles’ perspective this is just, there exists radical inequality between people, not all lives/families are as valuable as each other

- “Countless”, the number was not important to him, just that they were lesser men than him

- The question we are posed is whether Achilles’ value was so much greater than those who lost their lives for the sake of his wrath

- Significance of the bodies of the slain being eaten by birds or dogs

- Burying is to hand land over to the dead, reserve it for their use, remove it from the use of the living

- Some men are buried in the Iliad, but not all, and even some great men are unburied

- Agamemnon is in possession of the Chryseis, daughter of Chryses, the priest of Apollo; the priest is willing to give anything to get her back

- Agamemnon threatens the priest however and he runs away, and then calls a curse upon the Achaeans

- he seems not confident that Apollo will protect him; he shows a vulgar, low piety; “backscratching trade”

- Apollo wreaks havoc for 9 days, shoots arrows from afar and sends plague rats, ignominious ways to die

- Achilles calls the Achaeans to assembly on the 10th day; is he worried that his choice is being taken from him, and he may die at the hands of a plague rat?

- The plague and then assembly mirror, or are a microcosm of, the war itself (9 years + 1 year); also the cause of the war is perhaps mirrored here: Paris stealing Helen from Menelaus is like Agamemnon stealing Briseis from Achilles; there is a civil war breaking out within the Achaean camp, where Achilles has as much cause to war against Agamemnon, as the Achaeans have against the Trojans

- Why must Achilles consult the seer Calchas as to the cause of the Achaeans misfortunes, when it seems so obvious that it’s the wrath of Apollo?

- Is Achilles still at this point interested in preserving the chain of command and stability (a hard won good) in the Achaean camp? Therefore he approaches Agamemnon obliquely and respectfully through Calchas.

- However Achilles’ promise to Calchas that he will defend him against Agamemnon seems to counter this, since it is in a sense a boast of his fighting strength over Agamemnon’s.

- Calchas’ fear of retribution indicates that he cannot publicly speak truth at this sort of assembly

- Achilles is of course offended that Briseis is taken from him, but perhaps he would have been more insulted if Ajax’ or Odysseus’ woman were taken instead, since this would mean that they had received a greater prize than he.

- Achilles accuses Agamemnon of being a “devourer of his people”, that he doesn’t benefit the people, but it is not clear that the people benefit by Achillles in any way either

Book 2

Thucydides is the key to understanding the Catalogue of Ships; through him you can get a lot more out of the Catalogue

Book 3

- Book 3 contains two alternating themes of single combat between Paris and Menelaus, and the people within the city of Troy

- The two sides are marshalled and the Trojans are making loud, bird noises (bravado), while the Achaeans are silent and well-ordered (truer confidence in themselves)

- Opening scene is followed by a simile: “When the South Wind showers mist on the mountaintops, no friend to shepherds, better than night to thieves, you can see no farther than you can fling a stone. So dust came clouding, swirling from the feet of armies, marching at top speed, trampling through the plain.”

- South Wind is to the mist as the feet of the armies are to the dust. Just a colourful or poetic way of describing the dust?

- But why is the mist better than night to thieves? Unnecessary detail or pointing to something else important?

- The mist that is good for thieves is a beautiful pretext for something wicked, such as using Helen as an excuse for plundering and destroying Troy.

- When Paris is considering single combat with Menelaus, he mentions that the victor will not only get Helen, but also all her wealth; Helen is not all that is at stake

- Is this why the Trojans don’t just chuck Paris and Helen out, and avert the destruction of the city? Helen is a beautiful ornament to the city, but she also has great wealth.

- Agamemnon and Priam meet to cement the agreement that single combat between Paris and Menelaus will decide the war

- Agamemnon adds a term to the agreement that Priam has already heard from a herald: if red-haired Menelaus wins, the Trojans will hand over both Helen and all her wealth, but also pay reparations to the Greeks

- Doesn’t this make it very easy for both sides to keep fighting the war if Menelaus wins? For both sides to feel they got a bad deal?

- Even though the duel ends with Aphrodite spiriting Paris away, Agamemnon has done everything within his power to ensure that the war will continue and the Achaeans will possibly gain all of the wealth of Troy.

- Are the Achaeans the thieves protected by the mist? Pirates whose wickedness is veiled by the pretext of recapturing Helen?

- Priam speaks to Helen, asking her about the great champions of the Achaeans

- He learns that Achilles is not on the battlefield

- There are some funny parallels here between Helen’s activities in this scene and Homer’s own activities and especially the end of Book 2

- She is weaving a dark-red robe that displays the struggles between the Trojans and Argives, an image of the war, not unlike Homer’s poem

- At the end of Book 2, Homer asks the Muses to help him catalogue the ships, while here Priam asks Helen to catalogue the Greek champions

- Helen speaks very sparingly of Ajax when asked by Priam, immediately goes on to talk about others; Ajax similarly only receives two lines from Homer during the Catalogue of Ships; both agree that they ought to say very little about him for some reason

- In principle, the activity of singing or reciting a story is not a very masculine thing to do (compared to being a warrior); we ought not to conclude immediately that Homer was somehow effeminate, but there is a perhaps an angle throughout the Iliad on how war and the martial life are not as fulfilling as they ought to have been, as they are thought by some people

- What is the best way of life for a man? How different were Homer and Achilles’ lives?

Book 4

- At the end, there is a simile about a shepherd that again reflects on Homer and his activity as a poet

- Book 4 has three parts

- Scene in Olympus where the gods plan how to continue the war

- Athena leads the archer Pandarus to break the truce after the inconclusive duel between Menelaus and Paris

- Review of the troops, similar to the Catalogue of Ships in Book 2, and Helen’s Review to Priam in Book 3, but here there is more interactions between the reviewer Agamemnon and the reviewed

IMPERATOR

Enjoyed this thread: who is the real hero of The Iliad, Achilles or Hector?

Hector

- The model of chivalry

- The prefigurement of victory in defeat

- Engages in mortal combat with Achilles, a demigod, knowing he will die, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori

- Reveals the deficiencies of his culture’s values and points to something greater

- His duties are to his family, his people, and his city, defending them against foreign invasion

- Lacked the ambition of Achilles

- Patriarchal masculinity

- Dies for honour

Achilles

- The pagan understanding of the devil who wrestled against the gods but can never be one

- The Iliad is about the anger of Achilles

- Perfectly embodies his culture’s values

- Formidable but vengeful and self-indulgent

- The Greek, tragic, hubristic hero; understanding of Ancient Greece depends on seeing Achilles as the hero

- Lacked the higher purpose of Hector

- Favoured by the gods

- Glorious masculinity

- God-like, dies for glory

Other

- The question itself is flawed, The Iliad is not a Hollywood movie, each character in it was considered to have his own worthiness

- To ask the question itself is to make a Semitic interpretation of The Iliad

- Hector and Acchilles are epitomes of different kinds of worthy men

- Diomedes and Odysseus

- Aeneas, technically