Contents

Read in July and August 2021, the Cambridge University Press’ “Utopia: Latin Text & English Translation”, 1995 Edition (paperback reprint from 2006), eds. George M. Logan, Robert M. Adams & Clarence H. Miller

Sometimes seems serious, but more usually playful in tone. A very ambiguous book, written by a Catholic willing to die for the faith, but taken seriously by many in its suggestion of a kind of perfection achievable through the State.

St. Thomas More was born on Milk Street in the City of London on 7 February, 1478. He was sent to school at St. Anthony’s in Threadneedle Street. From about the age of twelve he served as a page in the household of John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor to Henry VII. While training at the Inns of Court, he lived for four years at the London Charterhouse, sharing as much of the monks’ way of life as was possible. He married Jane Colt in late 1504 or early 1505. She bore him four children (Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John) and died in 1511. That same year he married the widow, Alice Middleton.

From May – October, 1515, Thomas More was sent to Bruges as a member of a royal trade commission. Having considerable leisure, it was during this time he composed Utopia. At some point during this period he went to Antwerp to meet Peter Giles, to whom Erasmus had recommended him.

Thomas More succeeded the disgraced Cardinal Wolsey as Lord Chancellor on 26 October, 1529. He resigned on 15 May, 1532. On 13 April, 1534, he was summoned to Lambeth Palace and there asked to assent under oath to the Act of Succession, which he refused. He was imprisoned in the Tower of London from 17 April. His trial took place on 1 July, 1535. On 6 July, at 9 o’clock he was led out from the Tower, wearing a long beard which had never been his fashion. At the base of the scaffold he asked the Constable of the Tower, “See me safe up. For my coming down I can shift for myself.” His last words were, as he moved his beard out of the way, “Pity that should be cut; that has not committed treason.”

Introduction

- More’s handling of the problem of theft (at John Morton’s table) differs from other writers of the period in his holistic approach, not a single solution (e.g. sending wise counsellors to court) to such problems; theft is related to poverty with is related to many other societal problems; e.g. the enclosures had wide-ranging disastrous effects on society, labourers lose their livelihood

- Hythloday derived from Socrates who is described as peddling nonsense in the Republic

- “More” and Hythloday are perhaps different versions or facets of the author

- Seriocomic style of Utopia related to Lucian whom More translated

- Similar to the later Rabelais and Swift

- This tradition characterised by the phrase sēriō lūdere

- Hythloday believes that counsellors who seek to at least use their influence to moderate things, make them less bad are neither Christian nor practical

- Hythloday agrees with the Stoics here that the moral and expedient course are always the same

- This Stoic belief characterized a lot of early humanism

- Later Machiavellian humanists did not believe any more that honestas is the same as utilitas

- “Despite its abundant wit, Utopia is in fact a rather melancholy book. More evidently shared with St. Augustine (whose City of God he had expounded in a series of lectures about 1501) the conviction that no human society could be wholly attractive.”

- More’s joyous Latinity, it was very much a living language for him

- “More’s is an extremely eclectic Latin, bearing with it the mingled aromas of the marketplace, the pulpit, the law court, the classroom, the church father, the historians (like Sallust, who was so fond of archaisms) and the familiar letters of Cicero — who was not always as Ciceronian as we think. Though More gives some signs of using Latin as a second language, it was one with which he was joyously familiar; his Latin is full of ellipses, colloquialisms, half-rhymes, neologisms rubbing shoulders with archaisms, locutions drawn from one context and boldly adapted for use in another.”

More to Giles

- More is sorry for taking so long to send Giles the book; the discussion of when More finds time to write, amidst a busy career and domestic life, reminds me a little of J. R. R. Tolkien

Book I

- Hythloday and the Utopians are interested more in the Greeks than the Romans, who left us nothing valuable except Seneca (a stoic!) and Cicero, p. 45

- Monsters are very commonplace these days so we didn’t ask about them at all, “His de rebus avidissime rogabamus … omissa interim inquisitione monstrorum, quibus nihil est minus novum … nusquam fere non invenias, at sane ac sapienter institutos cives haud reperias ubilibet!” p. 48

- Start of the story of Hythloday at the table of John Morton, p. 54

- The lay lawyer wonders why there is still thievery when so many thieves are hanged

- Hythloday says that “haec punitio furum et supra justum est et non ex usu publico ”, p. 56

- It is not for the public or common good or use, besides going beyond what justice requires it disturbs the peace, à la Before Church and State

- Discussion of the enclosures starts on p. 62

- Sheep: “tam edaces atque indomitae esse coeperunt ut homines devorent ipsos”

- According to footnote, from 12th to 19th century

- Prophetic: “nondum sentitur totum hujus rei incommodum,” the full impact was even in 16th century not yet felt, p. 64

- Poverty lives side-by-side with luxury and extravagance, brothels, gambling, vain sports and pursuits, that lead to more poverty and thievery:

- “Has perniciosas pestes ejicite, statuite ut villas atque oppida rustica aut hi restituant qui diruere, aut ea cedant reposituris atque aedificare volentibus. Refrenate coemptiones istas divitum ac velut monopolii exercendi licentiam. Paucioresalantur otio, reddatur agricolatio, lanificium instauretur ut sit honestum negotium quo se utiliter exerceat otiosa ista turba,” p. 66

- “The friar and the fool: a merry dialogue” begins p. 76

- I think More is not a fan of friars, and wishes they’d return to monasticism and stability, ceasing from the mendicant life

- The fool (also called the parasite) is really annoyed with beggars and says that they should all become lay brothers of monasteries, or nuns

- The friar objects that even then not all beggars would be dealt with because there would still be friars

- No, says the fool, the Cardinal already covered you when he said vagabonds could be arrested and put to work, friars being the greatest vagabonds of all

- Hythloday is explaining what it would be like if he were an advisor to the King of France, how his ideas (e.g. leave Italy alone because France is almost too much to govern) would not go down well

- His tactics for dealing with England, p. 84, e.g. secretly encouraging banished noblemen with pretensions to the throne, are praised later when practised by the Utopians, p. 206

- “More’s” Aristotelian objections against communism, p. 104

- How can people live well where all things are common

- If there is no hope of gain for working, no hope of protecting what one has obtained, people will become lazy

- Respect for magistrates and for authority in general will be lost when men are not distinguished from each other in any way

- Scholastic theology often inappropriate, has its limits, doesn’t adapt itself to people and their situations, p. 94

- “More” suggests a different philosophy would be a better fit for counsellors of kings, that Ciceronian philosophy of decorum, i.e. propriety of words and actions

- Ancient conflict between rhetoric and philosophy, persuasion and truth

- “More”: “Nam ut omnia bene sint fieri non potest, nisi omnes boni sint, quod ad aliquot abhinc annos adhuc non expecto .” Adapting to a fallen world, p. 96

- The positive effect of the Utopians’ perpetual readiness to learn: “quod unum maxime esse reor in causa cur, quum neque ingenio neque opibus inferiores simus eis, ipsorum tamen res quam nostra prudentius administretur et felicius efflorescat”, p. 106

Book II

- The dignity of labour is a recurring theme throughout; inspired the Communists, but it really points to the monastic tradition

- Utopus, wishing to dig a channel between Utopia and the mainland, put both the conquered natives and his own soldiers to work, “ne contumeliae loco laborem ducerent”, p. 110

- Footnote, “the principal sources of this attitude are Christian; in particular, the monastic orders represented a paradigm of society in which all are workers. (Monasticism is the one European institution that the Utopians are said to admire (p. 221), and such Utopian institutions as their uniform dress (pp. 125, 133) and common meals (p. 141) — generally, their communal way of life — recall monastic rules.)”

- Size of the country families: “nulla pauciores habet quam quadraginta, quibus pater materque familias graves ac maturi praeficiuntur,” p. 112

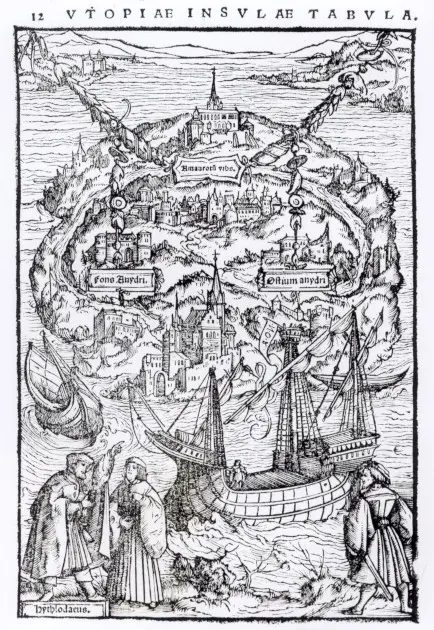

- The number of cities in Utopia is 54, the same number of counties in England and Wales (41 + 13 = 54) if Yorkshire’s three ridings are each counted, p. 112

De urbibus, ac nominatim de Amauroto

- The Utopians live in a cloister surrounding a garden: “Posterioribus aedium partibus, quanta est vici longitudo, hortus adjacet latus et vicorum tergis undique circumseptus. … Hos hortos magnifaciunt: in his vineas, fructus, herbas, flores habent tanto nitore cultuque ut nihil fructuosius usquam viderim, nihil elegantius,” p. 118

- Footnote states that some have seen similarities between Utopian and Roman houses, but the notable difference “lies in the fact that the Utopian courtyards are merged in the communal gardens.”

- “Nam domos ipsas uno quoque decennio sorte commutant,” the footnote says that Carthusians, such as the ones More lived with, also regularly exchanged their cells

De magistratibus

- Each group of 30 households elects a syphogrant each year to represent them; a tranibor, elected annually, presides over 10 syphogrants; all 200 syphogrants together elect the governor or princeps of Utopia, who holds office for life, unless suspected of tyranny, p. 122

- Syphogrants always talk matters over amongst themselves and with the households they represent, before presenting things to the senate

De artificiis

- Comment, p. 124, “Agricolatio communis omnium, quam nunc in paucos contemptos rejicimus”

- “Ars una est omnibus viris mulieribusque promiscua, agricultura, cujus nemo est expers.”

- “Hac a pueritia erudiuntur omnes, partim in schola traditis praeceptis, partim in agros viciniores urbi quasi per ludum educti ,” i.e. field trips out to learn through games; footnote: “both Plato and Aristotle stress the educational potential of games”, Plato, Laws 1.643C: “A man who intends to be a good farmer must play [in childhood] at farming.”

- Recreation after supper, they have two chess-like games:

- “One is a battle of numbers, in which one number captures another.”

- I would want to play this: “The other is a game in which the vices fight a battle against the virtues. The game is ingeniously set up to show how the vices oppose one another, yet combine against the virtues; then, what vices oppose what virtues, how they try to assault them with open force or undermine them indirectly through trickery, how the defences of the virtues can break the strength of the vices or skillfully elude their plots; and finally, by what means one side or the other gains the victory.”

- Probably a very dry joke on p. 128; the Utopians only work 6 hours a day, how is it possible that things get done, that they are productive and enjoy such a happy life? Because unlike in other countries there are no idlers, e.g. women who don’t do their share of the work. The editor wonders in a footnote, if all the Utopian women are working then who does the cooking, childcare, things women normally did in medieval society, etc. But I think the idea of women labouring as much as men would be so obviously a joke to the people of the 16th century. It’s only in the 20th/21st centuries that we miss this and see it as part of a perfect communist world.

De commerciis mutuis

- Reading at mealtimes like monks, p. 142, “Omne prandium cenamque ab aliqua lectione auspicantur quae ad mores faciat, sed brevi tamen, ne fastidio sit.”

- The marginal note says, “Id hodie vix monachi observant”

- A footnote says that the humanists were fond of this monastic custom, and More practiced it at his own table

De peregrinatione Utopiensium

- Carefree travel in the Utopian countryside, yet food and work are strongly bound, p. 144

- “Toto itinere, cum nihil secum efferant, nihil defit tamen, ubique enim domi sunt .”

- “Sed in quodcumque rus pervenerit, nullus ante cibus datur quam antemeridianum operis pensum aut quantum ante cenam ibi laborari solet absolverit.”

- Against the mendicant friars again

- 2 Thessalonians iii, 10: “Nam et cum essemus apud vos, hoc denuntiabamus vobis : quoniam si quis non vult operari, nec manducet.”

- Cities assist one another by supplying each others needs as free gifts, expecting nothing in return, p. 146

- “Ita tota insula velut una familia est,” and marginal note, “Respublica nihil aliud quam magna quaedam familia est.”

- The Utopians prefer to use mercenaries whenever possible to fight their wars, p. 146

- Anti-Christian, anti-chivalric

- Utopia firmly in the Iron Age

- Something symbolic about their contempt for gold and silver, “quis non videt quam longe infra ferrum sunt?”

- “Ex auro atque argento non in communibus aulis modo sed in privatis etiam domibus matellas passim ac sordidissima quaeque vasa conficiunt.”

- Apparently More expresses similar views in propria persona in two works written in the Tower, A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation and A Treatise upon the Passion

- A passage mocking the Scholastics, p. 156

- The Utopians have matched our own ancient philosophers in almost all subjects, but it seems they far from attaining the heights that our modern logicians have

- Mocks the Parva logicalia, late medieval treatises on logic of dubious value

- Utopians have no interest in astrology either, p.156-158; More himself wrote some poems mocking it

- More is apparently not a fan of hunting; the Utopians see it as an unworthy activity, p. 170; cf. also More’s poem about the rabbit caught in a trap, etc.

- Plato (and some of More’s contemporary humanists) on the other hand praised hunting as good exercise and good practice for war (Laws, VII.823B–824B)

- Utopian philosophy something of a rapprochement between Stoicism and Epicureanism (which Seneca sometimes embodied), discussion of this starts on p. 161

- Pleasure can arise from mysterious sources, p. 172, “Interdum vero voluptas oritur, nec redditura quicquam quod membra nostra desiderent, nec ademptura quo laborent, ceterum quae sensus nostros tamen vi quadam occulta sed illustri motu titillet adficiatque, et in se convertat, qualis ex musica nascitur.”

- Footnote on p. 179, the Utopians reject ascetic denial in order to strengthen oneself against possible future adversity, but More in other works takes for granted the efficacy of fasting in “taming of the flesh against the sin imminent and to come” (Confutation of Tyndale’s Answer)

De servis

- Utopian euthanasia, p. 186, see Professor David Jones’ lecture for the Newman Society Oxford below

- Footnote, absolutely not acceptable in Catholicism, More discusses the “wicked temptation” of suicide at length in A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation and cf. Hythloday’s earlier reference to God’s prohibition of self-slaughter, p. 69

- The world as a prison is a common theme in many of More’s works, e.g. Latin poem no. 119, “In hujus vitae vanitatem”

De re militari

- Footnote p. 207, the Utopians use assassinations, stirring up dissensions, encouraging pretenders with ancient claims, as ways of dealing with their enemies and avoiding open war; interesting to compare with the schemes of the corrupt councillors that Hythloday imagines in Book I (p. 85)

- Further explanation of the Utopians use of mercenary armies, on p. 208

- Hard to believe that More himself would have approved of such people as the Utopians employ, e.g. “quae sanguine quaerunt, protinus per luxum, et eum tamen miserum, consumunt.”

- Footnote explains that the Zapoletes sound an awful lot like the Swiss (was More also not a fan of the Swiss?)

- “Utopienses siquidem ut bonos quaerunt quibus utantur, ita hos quoque homines pessimos quibus abutantur,” translated as, “And the Utopians, as they seek out the best possible men for proper uses, hire these, the worst possible men, for improper uses.”

- Footnote on p. 211, mercenaries were known to commit atrocities, including the Sack of Rome in 1527 which More talked about in Dialogue Concerning Heresies; Erasmus says “there is no class of men more abject and indeed more damnable.

- One of the weird things in this book that are put into Hythloday’s mouth, and all the obvious 16th century objections are never raised; indeed we would probably have many fewer objections to these today, since we really like the idea of war by proxy (or at least robot mercenaries!)

De religionibus Utopiensium

- Suggestion that the Utopians who became Christians did so because they were impressed by the Christian monastic ideal, p. 220

- Atheist heretics in Utopia, tolerated but liberally encouraged: “Verum ne pro sua disputet sententia prohibent atque id dumtaxat apud vulgus. Nam alioquin apud sacerdotes gravesque viros seorsum non sinunt modo sed hortantur quoque, confisi fore ut ea tandem vesania rationi cedat.”

- Families and households have a monastic structure to them, p. 236

- “At in finifestis antea quam templum petunt, uxores domi ad virorum pedes, liberi ad parentum provoluti, pecasse fatentur sese, aut admisso aliquo aut officio indiligenter obito, veniamque errati precantur.”

- Utopian religious music and instruments described, p. 238, the sound and the subject match perfectly

Conclusion

- There is less than a page left when Raphael has finished his story, p. 246

- “More” thinks about the absurdities of the Utopians customs

- His chief objection is their communal living and moneyless economy, “vita victuque communi sine ullo pecuniae commercio”

- “More’s” view here consistent with Aristotle and his earlier speech against communism, p. 105, Aristotle says there is a connection between nobility and wealth (Politics IV.viii.9, V.i.7), magnificence is “suitable expenditure on a great scale” (Nichomachean Ethics IV.ii.1) and there is a necessary connection between money and the exercise of virtue.

- Thinks Raphael is tired now so they will go to supper, and he hopes they will find another time to discuss these matters more deeply

Videos I found about Utopia

Monasticism and More’s Utopia by Justine Brown’s Bookshelf

- The old London Charterhouse, where Thomas More lived for 3 years in the late 1490s, while studying at Lincoln’s Inn

- This was a crossroads in his life, discerning monasticism which attracted him greatly, or a more secular life

- The Charterhouse sheds some light on More’s Utopia

- Social arrangements on Utopia attempt to reconcile the two vocations that More felt, monasticism for married people

- Monasteries were the deep wells of Christendom, that built civilization all around them

- “Work and prayer” as the source of civilization

- More and Jane’s household was oriented towards prayer, fasting, and study as he sought to integrate monasticism into his married life

- More secretly wore the Carthusian hairshirt for the rest of his life

- More taught Jane classical languages and other subjects, and she was eventually able to converse in Latin with their guests

- He endeavoured to make his house at Chelsea a factory of civilization, where girls as well as boys received a classical education

- Utopia is like a shimmering mirage where it is difficult to pin down what was meant, how in jest it is

- The Utopians’ communal life and property held in common has been seen as proto-communism, but it points more to the monastic life, and to the life of the Apostles themselves

- Defamiliarization, putting forward one’s ideas by setting them in a fantastic context

- Utopians have identical clothing, cloister gardens, common dwellings, manual labour for all, intellectual work for those who are up to it, hospitality to travellers, etc., etc.

- The Utopians have a broadly Epicurean (based on pleasure, but not licentious) morality and philosophy, they are portrayed as being on the cusp of Christianity, having gotten to the god of the philosophers and just requiring some further revelation

- Unlike both monastics and Epicureans however, marriage is a core value

- Utopia could be a whole society of interconnected monasteries

Sir Thomas More: The Man Who Made Utopia by Justine Brown’s Bookshelf

- Modern usage of the word “utopia” has lost the οὐ-sense and kept only the εὐ-sense from More’s pun, which the original readers were meant to get straightaway

- Utopia is full of this playful oscillation between perfection and impossibility

- Many jokes remain untranslated in modern editions

- Suggest that the perfect does not exist, or that moments of perfection are fragile and fleeting

- We know from the 20th century that utopianism is a way fraught with peril

- We should set out to improve society with fear and trembling, keeping a tight hold on what we know about human nature and thriving

- More’s own personality was a mixture of dry humour, earnestness, and humility

- Utopia seems to reflect that, part joke, part intellectual exercise, part meditation

- Utopia a fiction about fiction, that encourages us to reimagine things, but warns us gently against credulousness

- The work’s irony was typical of its creator, and this is often missing from modern translations

- Ultimately a warning that the perfect place does not lie in this world

Thomas More’s Magnificent Utopia - Dr Richard Serjeantson by Gresham College

Gives a description of the book, and talk about the historical context. He goes through some of the ideas in the book. He contends that Utopia was the most “democratic” polity ever conceived at that point in history. A disappointingly liberal/enlightenment take on Utopia, after Justine Brown’s brilliant ideas.

Justine Brown on Thomas More’s “Utopia” and Christian Intentional Communities by The Distributist

St Thomas More Lecture: Thomas More and John Donne on ‘Assisted Dying’ - Professor David Jones, FHEA by Newman Society Oxford

- Thomas More is used by many advocates for “euthanasia” as an example of Christian approval of practice due to the passage in Utopia, Book II

- “Utopia” has come to mean an ideal or perfect society, but that was not More’s intention, rather he being deliberately playful with the similar sounding Greek “Good-place” and “No-place”

- More’s “No-place” is only partly a “Good-place”

- “More sought to imagine a pagan society that was seeking the Good, and what that might be like, but he actually believed in a world that was both better and worse than that. A world of Grace and sin. A world in which Christ died, but where the devil still prowls, for the ruin of souls.”

- Some Utopian customs were clearly ones that More personally rejected, e.g. divorce, tolerance of different religions, suicide when a person is no longer useful to society

- Historian Paul Green records Thomas More’s concern for people who have committed suicide or are tempted to

- A man in London, Richard Hunne, got into a dispute with a priest regarding death duty (mortuary fee) for his deceased infant son; the priest accused Richard of heresy, and he was imprisoned by the bishop, and found to have hanged himself

- Thomas More was apparently moved by this story, commented on it, and avoided sending others to the bishop’s prison, lest the same should happen

- And again, More met a man from Winchester, prone to despair and thoughts of suicide, and More counselled him and prayed for him, and kept his spirits up

- When More was in the Tower, the man again began to despair

- As More was being taken to the scaffold, the man pushed through the crowd to speak to More:

- Man: “Mister More, you know me. I pray you for the Lord’s sake help me. I am as ill troubled as I ever was.”

- More: “I remember thee full well. Go thy ways in peace and pray for me, and I will not fail to pray for thee.”

- And so long as the man lived he was no longer troubled by that temptation.

- More’s Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation, written in the Tower, contains and extended discussion of suicide, arguing that it should not romanticized, and that temptation to suicide must be resisted, by seeking both spiritual counsel, and a physician’s help to temper melancholy

- More’s own personal views on suicide are also found in Utopia, but not in Book II and the Utopians’ practices, but in Book I, where Hythloday attacks the unjust laws of England where even petty thieves are put to death:

- The argument there: God has not given us the right to take our own lives or the lives of others; if we men, by mutual consent, make manslaughter lawful in cases in which God has given us no example, then it frees people from the obligations of God’s law, giving preference to human law

- Regarding John Donne’s idea of pseudo-martyrdom, i.e. how in his opinion the Jesuits of his time were too in love with death

- Whatever one thinks about the Elizabethan Jesuits, Thomas More was not such a lover of death

- More sought to avoid execution while he could by discretion

- When he refused to take the Oath of Supremacy, he remained reticent about his reasons, and appealed to conscience

- Perhaps this was to spare the consciences of those who in their ignorance refused to swear the oath. He didn’t want to put people in danger before his own courage was tested.

- Thomas More (and John Donne) saw death however it should come as something to be accepted, “as a return to God, and as a trial that is common to all humanity”

- It is because of humanity’s solidarity in death, that suicide and assisted suicide cannot leave us unaffected

St. Thomas More: Man and Myth by Apostolic Majesty

It is paywalled, so I may have to give him some money some day in order to hear this.